On the eve of the day the war began last February, I produced a package which analysed the Russian military buildup around Ukraine. I was interviewing a military analyst from the Austrian armed forces. Bottom line: a full scale invasion was unthinkable a few weeks ago, but not impossible any more. Nevertheless, I went to bed that that day not considering that scenario likely. How wrong I was.

This major breaking news story, beginning in the middle of the night was not easy to handle. As ORF has no 24-hour news channel operation, starting an hour long special bulletin is not the easiest task. But, the fact that ORF has a relatively big network of correspondents paid off once more.

We opened a bureau in Kiev after the Euromaidan protests in 2014. Our correspondent Christian Wehrschütz, originally based in the Balkans, is an expert on Ukraine, knowing its people and the language. He was on assignment in Mariupol of all places when the invasion started. And he quickly became the face of ORFs coverage of the war, constantly on the move around the country. At the end of October last year, the hotel he stayed in was hit by a Russian bomb. He and his team were unharmed.

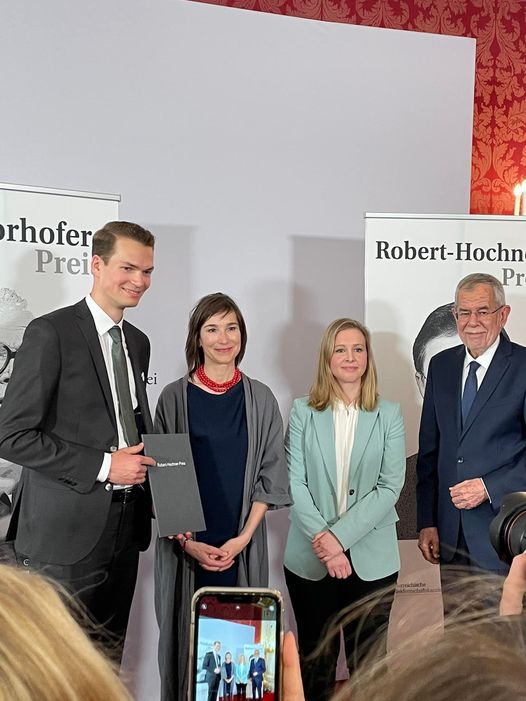

To have a fully equipped bureau in Moscow was also a huge advantage. With two correspondents on the ground, and a third one stepping in on a regular basis, we were able to cover the Russian perspective as well. After briefly calling them back to Vienna when the government released the censorship law, the team decided to head back to Russia despite difficult circumstances. Both our Moscow team (Paul Krisai, Miriam Beller and Carola Schneider) and ORFs Ukraine correspondent won awards since the beginning of the war, resonating the high regard by the audience.

The Russian aggression also brought a whole range of domestic and economic issues on the agenda. First and foremost, inflation and the cost-of-living crisis hit Austria like any other country. The government reacted with a package of measures costing at least six billion Euros. But while inflation went down in some other European countries, it remained on the highest level for seven decades. On top of that, Austria was heavily dependent on Russian Energy supplies when the war started, struggling to find alternatives.

While the Refugee crisis was a controversial topic in the political discussion back in 2015, Austria welcomed around 60.000 people from Ukraine. They were considered as “neighbors” and are widely accepted by the public. Solidarity seems to stay at a high level. Especially at the beginning of the war, our news department focused very much on the refugee story, sending reporters to Poland, Romania, and Moldova as well as Lviv, to cover Ukrainians fleeing inside their country. Continuing a long tradition, ORF launched its famous “Nachbar in Not” (“neighbor in need”) campaign, collecting donations for those in need in Ukraine.

Another ramification of the Ukraine war is a renewed debate about Austria’s neutrality. Deeply rooted in the country’s identity and very popular among the population, there is no political will in sight to get rid of it and join NATO, like Sweden and Finland did. But there are initiatives how to interpret neutrality differently – with the possibilities of EU membership. While Austria has supported Ukraine with more than half a billion Euros, mostly in humanitarian aid, weapon deliveries are impossible. Members of the government repeatedly stressed the importance of keeping communication channels with Russia open. Federal chancellor Karl Nehammer was one of the very few western leaders to visit President Putin after the beginning of the invasion. While Austria is very keen to maintain military neutrality, this does not mean political indifference. Austria supports EU sanctions against Russia and repeatedly pledged solidarity with Ukraine.

It is stating the obvious: Covering the Ukraine war will be a major challenge for us at ORF news for years to come, as it is for everyone. But the context is getting broader: What will India’s policy be moving forward? Are we in a new Cold War, this time with China? These are major geopolitical questions, but the battlefield is still in Ukraine.

Showing the suffering, telling the stories of those most affected by Russian attacks, being on the ground to witness everything and keeping up public interest for the war will be on the news agenda for a long time. It is an old media saying that when audiences lose interest the longer a story is in the news. But with the first full scale invasion in Europe since the end of World War II, there can be no going back to normal. The story is too important.